A meltdown is a condition where the youngster with ASD level 1, or High Functioning Autism, temporarily loses control due to

emotional responses to environmental factors. It generally appears that the youngster has lost control over a single and specific issue, however this is very rarely the case.

Usually, the problem is the accumulation of a number of irritations which could span a fairly long period of time, particularly given the strong long-term memory abilities of young people on the autism spectrum.

Why The Problems Seem Hidden—

ASD kids don't tend to give a lot of clues that they are very irritated:

- Often ASD child-grievances are aired as part of their normal conversation and may even be interpreted by NTs (i.e., neurotypicals, or people without autism) as part of their standard whining.

- Some things which annoy ASD kids would not be considered annoying to NTs, and this makes NT's less likely to pick up on a potential problem.

- Their facial expressions very often will not convey the irritation.

- Their vocal tones will often remain flat even when they are fairly annoyed.

What Happens During A Meltdown—

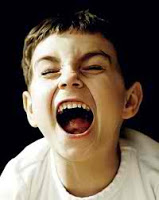

The meltdown appears to most people as a temper tantrum. There are marked differences between adults and kids. Kids tend to flop onto the ground and shout, scream or cry. Quite often, they will display violent behavior such as hitting or kicking.

In adults, due to social pressures, violent behavior in public is less common. Shouting outbursts or emotional displays can occur though. More often, it leads to depression and the ASD man or woman simply retreats into themselves and abandons social contact.

Some ASD kids describe the meltdown as a red or grey band across the eyes. There is a loss of control and a feeling of being a powerless observer outside the body. This can be dangerous as the ASD youngster may strike out, particularly if the instigator is nearby or if the "Aspie" is taunted during a meltdown.

Depression—

Sometimes, depression is the only outward visible sign of a meltdown. At other times, depression results when the ASD youngster leaves the meltdown state and confronts the results of the meltdown. The depression is a result of guilt over abusive, shouting or violent behavior.

Dealing With Meltdowns—

Unfortunately, there's not a lot you can do when a meltdown occurs in a child on the autism spectrum. The best thing you can do is to train yourself to recognize a meltdown before it happens and take steps to avoid it.

Example from one mother: "ASD kids are quite possessive about their food, and my autistic child will sometimes decide that he does not want his meat to be cut up for him. When this happens, taking his plate from him and cutting his meat could cause a full-blown meltdown. The best way to deal with this is to avoid touching it for the first part of the meal until he starts to want my involvement. When this occurs, instead of taking his plate from him, it is more effective to lean over and help him to cut the first piece. Once he has cut the first piece with help, he will often allow the remaining pieces to be cut for him."

Once the youngster reaches an age where they can understand (around age 4 or so), you can work on explaining the situation. One way you could do this would be to discreetly videotape a meltdown and allow them to watch it at a later date. You could then discuss the incident, explain why it isn't socially acceptable, and give them some alternatives.

One adult "Aspie" stated the following:

"When I was little, I remember that the single best motivation for keeping control was once when my mother called me in after play and talked about the day. In particular, she highlighted an incident where I had fallen down and hurt myself. She said, 'Did you see how your friend started to go home as soon as you fell down because they were scared that you were going to have a meltdown?' She went on to say, 'When you got up and laughed, they were so happy that they came racing back. I'm proud of you for controlling your emotions.' That was a good moment for me that day. It really gave me some insight into how I tended to respond quickly without much forethought. I carried this with me for years later and would always strive to contain myself. I wouldn't always succeed, but at least I was trying."

Meltdowns And Punishment—

One of the most important things to realize is that meltdowns are part of the ASD condition. You can't avoid them; merely try to reduce the damage. Punishing an ASD youngster for a meltdown is like punishing someone for swearing when they hit their thumb with a hammer. It won't do any good whatsoever and can only serve to increase the distance between you and your youngster.

In addition, meltdowns aren't wholly caused by the current scenario, but are usually the result of an overwhelming number of other issues. The one which "causes" the meltdown is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Unless you're a mind reader, you won't necessarily know what the other factors are, and your ASD youngster may not be able to fully communicate the problem.

Every teacher of ASD students and every mom or dad of an ASD child can expect to witness some meltdowns. On average, meltdowns are equally common in boys and girls, and more than half of autistic kids will have one or more per week.

At home, there are predictable situations that can be expected to trigger meltdowns, for example:

- bath time

- bedtime

- car rides

- dinner time

- family activities involving siblings

- family visiting another house

- getting dressed

- getting up

- interactions with peers

- mom or dad talking on the phone

- playtime

- public places

- visitors at the house

- watching TV

Other settings include:

- answering questions in class

- directives from the teacher

- getting ready to work

- group activities

- individual seat work

- interactions with other children

- on the school bus

- the playground

- transitions between activities

From time to time, all ASD kids will whine, complain, resist, cling, argue, hit, shout, run, and defy authority figures. Meltdowns, although normal, can become upsetting to parents and teachers because they are embarrassing, challenging, and difficult to manage. Also, meltdowns can become particularly difficult to manage when they occur with greater frequency, intensity, and duration than is typical for the age of the ASD kid.

There are nine different types of temperaments in kids on the spectrum:

1. Distracted temperament predisposes the kid to pay more attention to his or her surroundings than to the caregiver.

2. High-intensity level temperament moves the kid to yell, scream, or hit hard when feeling threatened.

3. Hyperactive temperament predisposes the kid to respond with fine- or gross-motor activity.

4. Initial withdrawal temperament is found when kids get clingy, shy, and unresponsive in new situations and around unfamiliar people.

5. Irregular temperament moves the kid to escape the source of stress by needing to eat, drink, sleep, or use the bathroom at irregular times when he or she does not really have the need.

6. Low sensory threshold temperament is evident when the kid complains about tight clothes and people staring and refuses to be touched by others.

7. Negative mood temperament is found when kids appear lethargic, sad and lack the energy to perform a task.

8. Negative persistent temperament is seen when the kid seems stuck in his or her whining and complaining.

9. Poor adaptability temperament shows itself when kids resist, shut down, and become passive-aggressive when asked to change activities.

Around age 2, some ASD kids will start having what I refer to as "normal meltdowns." These bouts can last until approximately age 4. Some parents (thinking in terms of temper tantrums) mistakenly call this stage "the terrible twos," and others call it "first adolescence" because the struggle for independence is similar to what is seen during adolescence. Regardless of what the stage is called, there is a normal developmental course for meltdowns in children on the autism spectrum.

Children on the spectrum during this stage will test the limits. They want to see how far they can go before mom or dad stops their behavior. At age 2, ASD kids are very egocentric and can't see another person’s point of view. They want independence and self-control to explore their environment. When they can't reach a goal, they show frustration by crying, arguing, yelling, or hitting. When their need for independence collides with the parents' needs for safety and conformity, the conditions are perfect for a power struggle and a meltdown.

A meltdown is designed to get the parents to desist in their demands or give the child what he or she wants. Many times, ASD kids stop the meltdown only when they get what is desired. What is most upsetting to parents is that it is virtually impossible to reason with ASD kids who are having a meltdown. Arguing and cajoling in response to a meltdown only escalates the problem.

By age 3, many young people on the spectrum are less impulsive and can use language to express their needs. Meltdowns at this age are often less frequent and less severe. Nevertheless, some preschoolers have learned that a meltdown is a good way to get what they want.

By age 4, most ASD kids have the necessary motor and physical skills to meet many of their own needs without relying so much on the parent. At this age, these young people also have better language that allows them to express their anger and to problem-solve and compromise. Despite these improved skills, even kindergarten-age and school-age ASD kids can still have meltdowns when they are faced with demanding academic tasks and new interpersonal situations in school.

It is much easier to “prevent” meltdowns than it is to manage them once they have erupted. Here are some tips for preventing meltdowns and some things you can say:

1. Avoid boredom. Say, “You have been working for a long time. Let’s take a break and do something fun.”

2. Change environments, thus removing the child from the source of the meltdown. Say, “Let’s go for a walk.”

3. Choose your battles. Teach them how to make a request without a meltdown and then honor the request. Say, “Try asking for that toy nicely and I’ll get it for you.”

4. Create a safe environment that these children can explore without getting into trouble. Childproof your home or classroom so they can explore safely.

5. Distract them by redirection to another activity when they meltdown over something they should not do or can't have. Say, “Let’s read a book together.”

6. Do not "ask" ASD kids to do something when they must do what you ask. Do not ask, “Would you like to eat now?” Say, “It's dinnertime now.”

7. Establish routines and traditions that add structure. For teachers, start class with a sharing time and opportunity for interaction.

8. Give these children control over little things whenever possible by giving choices. A little bit of power given to the kid can stave-off the big power struggles later (e.g., “Which do you want to do first, brush your teeth or put on your pajamas?”).

9. Increase your tolerance level. Are you available to meet the ASD kid’s reasonable needs? Evaluate how many times you say, “No.” Avoid fighting over minor things.

10. Keep a sense of humor to divert the child's attention and surprise him or her out of the meltdown.

11. Keep off-limit objects out of sight and therefore out of mind. In an art activity, keep the scissors out of reach if the child is not ready to use them safely.

12. Make sure that ASD kids are well rested and fed in situations in which a meltdown is a likely possibility. Say, “Dinner is almost ready, here’s a cracker for now.”

13. Provide pre-academic, behavioral, and social challenges that are at the ASD kid’s developmental level so that he or she doesn't become frustrated.

14. Reward them for positive attention rather than negative attention. During situations when they are prone to meltdowns, catch them when they are being good and say things like, “Nice job sharing with your friend.”

15. Signal them before you reach the end of an activity so that they can get prepared for the transition. Say, “When the timer goes off 5 minutes from now, it will be time to turn off the TV and go to bed.”

16. When visiting new places or unfamiliar people, explain to the child beforehand what to expect. Say, “Stay with your assigned buddy in the museum.”

There are a number of ways to “handle” a meltdown that is already underway. Strategies include the following:

1. Hold the ASD kid who is out of control and is going to hurt himself or herself (or someone else). Let the child know that you will let him or her go as soon as he or she calms down. Reassure the child that everything will be all right, and help him or her calm down. Moms and dads may need to hug their Aspergers kid who is crying, and say they will always love him or her no matter what, but that the behavior has to change. This reassurance can be comforting for an Aspergers kid who may be afraid because he or she lost control.

2. If the youngster has escalated the meltdown to the point where you are not able to intervene in the ways described above, then you may need to direct the child to time-out. If you are in a public place, carry your child outside or to the car. Tell him that you will go home unless he calms down. In school, warn the student up to three times that it is necessary to calm down, and give a reminder of the rule. If the student refuses to comply, then place him in time-out for no more than 1 minute for each year of age.

3. Remain calm and do not argue. Before you manage her, you must manage your own behavior. Punishing or yelling at the child during a meltdown will make it worse.

4. Talk with the child after he has calmed down. When he stops crying, talk about the frustration the he has experienced. Try to help solve the problem if possible. For the future, teach the child new skills to help avoid meltdowns (e.g., how to ask appropriately for help, how to signal an adult that he needs to go to “time away” to “stop, think, and make a plan” ...and so on). Teach the Aspergers kid how to try a more successful way of interacting with a peer or sibling, how to express his feelings with words, and recognize the feelings of others without hitting and screaming.

5. Think before you act. Count to 10 and then think about the source of the ASD kid’s frustration, the child’s characteristic temperamental response to stress (e.g., hyperactivity, distractibility, moodiness, etc.), and the predictable steps in the escalation of the meltdown.

6. Try to intervene before the youngster is out of control. Get down at her eye level and say, “You are starting to get revved up, let's slow down.” Now you have several choices of intervention.

7. You can ignore the meltdown if it is being thrown to get your attention. Once the ASD kid calms down, you can give the attention that is desired.

8. You can place the youngster in "time away." Time away is a quiet place where he goes to calm down, think about what he needs to do, and with your help, make a plan to change the behavior.

9. You can positively distract the child by getting her focused on something else that is an acceptable activity (e.g., remove the unsafe item and replace with an age-appropriate game).

Post-Meltdown Management—

1. Do not reward the child after a meltdown for calming down. Some kids will learn that a meltdown is a good way to get a treat later.

2. Explain to the child that there are better ways to get what she wants.

3. Never let the meltdown interfere with your otherwise positive relationship with your child.

4. Never, under any circumstances, give in to a meltdown. That response will only increase the number and frequency of the meltdowns.

5. Teach the youngster that anger is a feeling that we all have, and then teach her ways to express anger constructively.

Best Comment—

My name is Sharon, I have been with Elliott for over ten years and we have a son Brandon who is 6 yr old. They both have aspergers syndrome we are awaiting Brandon’s appointment with the paediatrician consultant for diagnosis, but I am 110% sure it will be aspergers. I am feeling in the thick of it of late I have and am constantly looking for local support and forums online etc to reach out for guidance and any support also to offer my own support to others. I am a person centred therapist and in the past have worked in supporting children and adults on the autistic spectrum, I do have a good insight into the autistic spectrum but nothing prepares you for how it feels actually living 24/7 with it.

Firstly the biggest part for me is the heart break and hurt I feel for my son, then the worry and concern how he will get along in life. I am very pro active and of late have worked well with school to best advise them how we support Brandon’s needs it’s been an uphill struggle for the last year especially as they don't seem to have the knowledge or the amenities to support him.

I have been called to school several times of late because of his "disruptive" behaviour,, basically his stimming he does get louder if in a louder environment the teachers know this is a trigger and he is left alone to deal with this instead of being prepared for a change of noise or scenery or even a much needed teaching assistant who could work alongside him. If he gets too disruptive he is taken out of the class environment for "time out" is this a good way of dealing with it? As we have told school time out at home is if he is naughty, which generally he is never naughty. we have what we call quiet time at home where sometimes when he feels over load we just find a quiet place to sit together and relax or read whatever he wants really but it brings him down and more settled to cope better.

Again it will mean another meeting or ten..... To resolve or make a better learning environment for Brandon. They say they can’t do anything till he’s been statemented and funded for an assistant or further support. But they will assist him as best they can and I do feel listened to but there is of late something new nearly every day that needs adaption which imp fine with I am aware he defiantly needs some support. I have been on an emotional roller coaster.

It feels so isolating as support around this neck of woods is minimal. Brandon’s upset of late is his lack of friends he just wants his family to be at school all day every day his words because we love him! So the social aspect this is. So I discussed with head teacher and she has set a buddy system up for him its yet to be seen to be working, as I know how difficult it is for Brandon to mix and communicate with his peers and when he does he gets rejected.

We have tried so many routes with this he seems to connect with kids in play areas as he and they are generally being quite boisterous but its time limited so he feels less pressure. We are also in process of groups i.e. dancing as he loves to dance (street dance) and maybe other recreations of his choice. It feels like a very long a winding road what we are on I know I haven't spoke much bout Elliott having spent ten years with him would have thought Brandon’s aspergers may come easier to me understanding wise yes but on a personal level it’s so upsetting.

Other points are his eating habits he is a very bland eater and eats the same few foods we supplement with vitamins he is quite small in frame but eats quite well the foods he does enjoy think they call it the beige diet he has no colour in his food at all (pasta, no sauce, chicken nuggets, crisps plain flavour, crumpets, bread, some types of rice, certain chocolate, milk, Yorkshire puddings) there’s a few more but as you can see limited. We have tried so many different ways to entice him I would be grateful if you could give me any tips.

Feels like I am going on now, the list goes on his sensory issues really do dictate to him and us how the day goes sometimes, and he is becoming more and more aware of his stims and repetitive behaviour today its clapping and repeating words it was a machine gun noise (constantly)and random moves it varies from day. I feel I need more guidance in how to help/support Brandon. The melt downs are becoming more and more but he only does this with his dad I have a calming effect as soon as he starts in melt down they pretty much calm after I’ve been around him a few minutes. The routines he has etc seem to help a lot too.

If you can pull anything out of this letter and feedback I would be grateful there will be things I have missed but feel free to ask me any further questions. He also as 3 older step siblings 15, 19, 21 and they are very loving and supportive with him and very understanding. He as a great relationship with all of us in our family unit. Feels like the outside world is a daunting prospect right now.

More comments below...

.jpg)